Day 1

It was 8:30 a.m. when we lifted our much-burnt rear ends off the seats of the Turk Hava Yoleri (Turkish Airlines) aircraft. The 14-hour flight from Singapore to Istanbul had done much damage to our backsides. Fortunately, the good weather (about 15 degrees Celsius) in Istanbul helped cool off the cooked effect in quick time. So, by the time we finished immigration and entered the lounge of the Ataturk Airport, our minds no longer lingered on our damaged derrières.

The first thing to do was to change currency. Change currency we did, and became instant millionaires. A $100 bill got us about 13 million Turkish Lira. Then, we had to book into a hotel. Erdal, the man at the Avias Hotel Booking Center in the airport lounge offered a double bed and breakfast for $50 a day, free transport to the hotel included. We booked a room for two days and were asked to wait for the pickup van to arrive.

Turkish men were smartly turned out. The westernization of Turkey by the great Ataturk Mustafa Kemal shows in their clothing. The men are usually wear suits or at least odd-coats. The cool climate of Istanbul requires some form of heavy clothing. The women’s attire, however, varies considerably. The older, more orthodox Muslim women wear the ubiquitous veil. The younger generation is mostly dressed in jeans or slacks. Some are fashionably dressed in knee length skirts and stockings.

Cigarette smoking is very common the Turkish men. The peculiar looking ashtray stationed beside waiting chairs cannot be missed. It is a large stainless steel pan mounted on a pedestal. It gives out a pall of smoke because of all the cigarettes that are not stubbed out burning in it.

The journey to Hotel Sahane took us about 45 minutes through the traffic-congested highways and crowded streets of Istanbul. About one-third of the people of Turkey live in greater Istanbul whose population is about 15 million. As our van meandered through the milieu we were entertained by the lilting music that the westerners call Arabesque. A particularly catchy tune took my fancy and grew on me until the end of our trip.

At the Sahane’s front desk, we were given our room key that looked more like a chisel. As we entered our room, we were surprised to see a few suitcases on the bed. There was already an occupant in the room whose existence the hotel owner somehow seemed not to know. The bellboy rushed back to find us a new room. No sooner had we got inside than there was a noise at the door from the outside — of keys being turned and somebody trying to get in forcefully. I opened the door just in time to see a man retreating apologetically. It appeared that people were always keen to try other people’s rooms.

We had a late breakfast of Turkish bread, boiled eggs, butter, Turkish cheese and fresh olives, all washed down with strong and supposedly digestive Turkish coffee. We walked out of the hotel contented, and armed with my camera to shoot at sight. As we walked along the road taking in the cool but smoke and dust-filled air, I noticed a particular brand of Turkish hawker who catches your eye because of his colorful attire and all the paraphernalia he carries but cheats you in no uncertain terms if he comes to know you are a tourist. He is the mobile Sherbet vendor. The way he pours the juice from his shapely tankard that he carries on his back in one swift motion is a sight to behold. But he is never happy with what you pay him and makes you feel you should never have drunk the stuff in the first place.

Istanbul has acquired various names over the past millennia. It was the Byzantanium of the Greeks. It was then the Constantinople of the Christians. And finally, it was Istanbul of the Islamic Ottoman Turks. Over all these years it has been a major trading center between the West and the East. This is because of the Bosphorus Strait the Turks call Bogazici that connects the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. Bogazici splits Istanbul into two parts, the Asian side and the European side. And then there is the Golden Horn (called Halic), another waterway that again splits the western part of Istanbul. The confluence of the Bogazici and the Halic is host to a great buzz of ships that arrive from and depart to various parts of the world. We were so taken by this place we went there at least once everyday of our stay in Istanbul.

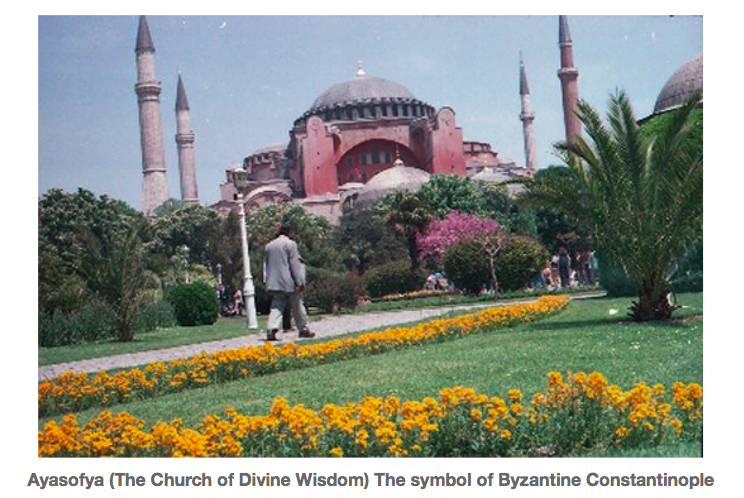

Not far from the coast of the Bogazici is the Ayasofya Museum, also called the Church of the Divine Wisdom, situated in an area called Sultanahmet. It is a church-turned–mosque-turned-museum. It is one of the greatest buildings of the world, built during the Byzantine period by the architect Ayasofya. As you enter the mammoth place you feel cool and tranquil. One can feel the quietness in the place in spite of all the tourists. The Ottoman Turks converted the church into a mosque with big circular Islamic monograms hanging from the walls and ceilings.

The Blue Mosque is just opposite the Ayasofya. Its exterior is thought to be the last word in classical order and harmony. It has a cascade of domes with six minarets (sharp, very tall columns) piercing the sky. The mosque was built by a pupil of the celebrated Ottoman architect Sinan. The Muslims wash before prayer at the water taps in the covered arcades by the sides of the mosque. When we were in the mosque, we were constantly hounded by carpet and Kilim sellers to visit their shops nearby. There was one man who wanted me to meet (for unfathomable reasons) an American who had turned a priest and was a permanent resident of the mosque for the past 14 years.

The Hippodrome, a large area in between the mosque and the museum, has many old columns and pillars with Greek and Roman inscriptions on them. This place was more interesting to me than the interiors of the mosques because of the crowd congregated there. The locals lazed in the shades of the trees eating large doughnut shaped buns, smoking cigarettes, reading papers, smooching their loved ones, or just doing nothing.

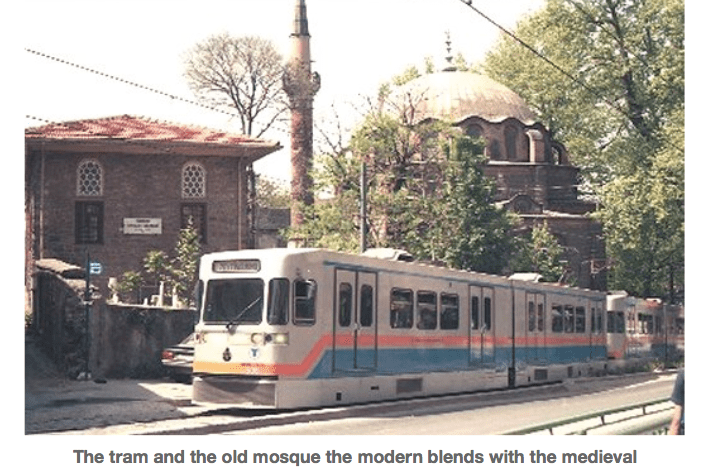

From Sultanahmet we walked to the coast of the Bogazici along the tracks of the local trams which are Turkey’s version of Singapore’s MRT. However, the difference is that the trams run on the same roads that the buses, taxis, bicycles and wheelbarrows share. The whole setup seemed very peculiar and funny to us.

The Bogazici is the place for an avid photographer. It is also a place for the connoisseur of fish food. I ate a long, tasty fish that they call Balik, fried and sandwiched in large slices of Turkish bread with just a hint of salt and lime. The fish is sold off a boat from which they catch the fish fresh off the Bogazici waters. We spent quite a lot of time there munching the Balik, watching people munching the Balik who were watching other people munching the Balik.

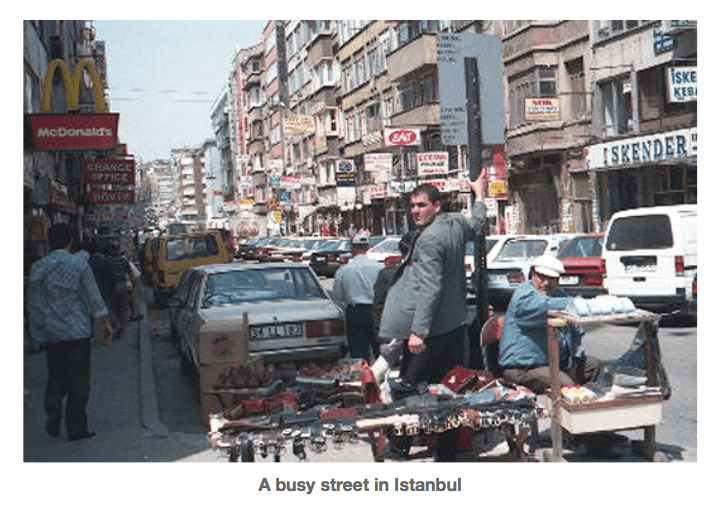

We then took a tram back to Aksaray where our hotel was situated. We were so tired after all the walking in the morning that we fell asleep immediately. It was only 6:30 p.m. I woke up at 10 p.m. again and went out in the chilly gale to get something to eat. As I was returning from McDonalds, I was accosted by a man who said, “Mister, very fine girl, only 3 milyon.” When I returned to the hotel and told Vani about this, she said, “He didn’t know you already have a fine girl.”

Day 2

We were awake by 6 a.m. The jet lag of 5 hours between Singapore and Turkey had set our biological clocks awry. We then had a really long breakfast spending more than half an hour on it. I started with fresh green olives, and then ate three boiled eggs, not to mention a heap of Turkish bread and lumps of butter and cheese. The cool weather, the slightly sour olives, and the intermittent doses of black Turkish coffee used to make me go wild on the breakfast. So much so, one day, I remember, I had two breakfasts in 2 hours. The cool weather also makes smoking extremely pleasurable. I had picked up the habit again, tempted by watching the Turkish men smoke. For Vani, of course, this was very worrying.

We took a tram to the Eminonu station from where we planned to catch a ferry to glide along the Bosphorus. The trams are extremely crowded during the morning hours. The ticket costs 40,000 Lira irrespective of the distance. We used the tram so much we still remember the names of the stops: Eminonu, Sirkezi, Gulhane, Sultanahmet, Cemberlitas, Universite, Lalane, Aksaray…

Our guidebook suggested that a trip on the Bosphorus should never be missed however short your visit to Istanbul. I concur. Ferries leave from Eminonu to steam past the great palaces and mosques that line the Bosphorus. The ferry usually stops at five villages along the way. The rich of Istanbul have built beautiful houses called Yalis that decorate the shores.

The interesting thing about the Bosphorus trip is the pendulous motion of the ferry from Asia to Europe and back to Asia. You will hear people (especially Americans) screaming with delight, “Oh, we are in Asia now; Oh, we are in Europe now.”

The wind on board was very chilly. I had advised Vani to wear her sweater and jacket. She declined saying she could bear the cold. Pretty soon she started shivering, but she did not put on her sweater. To prove her point, you see. I was very snug in my turtleneck T-shirt and jacket. Very soon she accepted defeat and put on her sweater.

On board, I met a Swiss named George-something, who said, “Isn’t it very chilly?” This was a common remark that everybody started conversation with on the ferry. I said, “You should be used to the cold in Switzerland.” He just laughed and asked which part of India I came from, and when I said Bangalore, he said he was going there in a couple of weeks. George sells textile machinery to many Indian companies, especially in Bangalore and Madras. He was polite enough to say he liked working with the Indians. Wonder if he spoke what he felt.

The ferry stops at Kanlica, Yanikoy, Sariyer and Rumeli Kavagi villages. At the end of the journey that took about one and half hours, we got down at a village on the Asian side called Anadolu Kavagi. A 21-year-old American girl, Pat, who had become very friendly, said she will tag along with Vani and me. Pat studies in a college in Portland (Oregon) and interestingly had studied one year of Hindi. She was on a six-month tour of east Europe which she said is cheaper. She had been to all the inexpensive places like Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Austria. She was on a three-week trip to Turkey. She had managed well in Istanbul, primarily on Turkish bread, and $4-a-day accommodation at the YMCA.

We had 3 hours to spend in the village. As we walked we saw houses that resembled the one I lived in at Hunsur in India, with big front and back yards surrounded by a bamboo fence. As we walked to the hilltop, a big sheep dog started following us for no apparent reason. I wondered if I had started looking like a ram with my beard just sprouting. We reached the Genoese castle above the village. It is actually Byzantine as the carvings and Greek inscriptions on the broken tower and walls reveal. My guidebook says it was known as the fortress of heroin and that it served as the naval headquarters for the Bosphorus. It is in a strategic position with a clear view of the Black Sea.

We saw a group of boisterous youth playing a kind of game that we used to play in school. One bends forward with one’s back horizontal while the rest jump off pushing down with their hands. There were sheep grazing on the hilltop while the shepherd was smoking and looking yonder. The whole setup, Pat said, looked like the English countryside.

When we were coming down the hill, we saw the Turkish Militia everywhere, handsomely uniformed and looking dangerous. Vani started taking pictures of Pat and me in front of their barracks. Pat then told us how she was caught in Bulgaria taking pictures of soldiers and was taken in for questioning and detained for a long time.

We came down the hill and decided to eat. The villages are known for their excellent harbor-front cafes. I ordered Tuborg beer, while the ladies had water. I ordered some mackerel for myself and a salad of very fresh tomatoes, onions and cucumbers, yogurt and Turkish Choy for Vani. Pat exclaimed about the high prices and decided to have some meatballs. She ended up eating most of our bread. I understood how she managed so well with little money.

Day 3

The previous evening we had visited the railway station at Cirkesi and inquired about train timings to various places in Turkey like Izmir, Ankara (the Capital), Pamukkale and Canakkale. We were always telling each other that we enjoyed train journeys. We wanted to go on a long train journey and see the countryside, the people and also to just enjoy the whole affair. We debated for a long while in the station the merits of visiting various places. We finally decided to go on the Pamukkale Express.

Today, first thing in the morning we went to the train station again and booked 2 tickets to Pammukale and back. The lady at the counter had a face as fresh as morning dew, I thought, and repeatedly used the words “possible” and “no problem” to our questions. She tried hard to explain things to us in English. French is a better-known foreign language in Turkey, and all I knew of French was “Je ne parle pas Francais” and “Merci.”

The train would leave this evening at 6:10. Before that we decided to visit the famous Topkapi Palace. Topkapi was the residence of the Ottoman Sultans for 400 years. Topkapi, as my guidebook says, means Cannon Gate. It is a vast and rambling palace and at its peak it had 5,000 inhabitants — slaves, cooks, government officials, apprentices as well as Sultans and their families and concubines.

We changed some currency (for the Pamukkale trip) and bought tickets at the gate of Topkapi. As we walked along the tree-lined road that leads to the palace entrance, we had very little idea of how big and complex the interiors of the palace were. As we entered, we saw the imperial treasury housing the glittering collection of emeralds, pearls, necklaces and the famous handle of the ‘Topkapi Dagger’. Opposite this is the imperial kitchen that looked more like the kitchen of a large marriage choultry in India. There were old brass and bronze vessels, large ladles, glass and silver, and the most beautiful of them all was the Chinese and Japanese ceramic collection. The Sultans were supposed to have a passion for chinaware which was imported via the arduous Silk Road. Then there was the imperial costume collection which had a lot of salwars that the Sultans wore, and which Vani wished she was given so that she could get them altered to fit her.

Each courtyard in the palace is supposed to be more private than the previous. The outer courtyard, according to my guidebook, contained bakeries, hospitals, porters’ and carriers’ quarters. The next courtyard was reserved for government business. It is called the courtyard of the Divan (a word used even in imperial India). It has a fountain at the center surrounded by flowers and a lawn.

The entrance to the harem, the place I wanted to visit the most but failed for want of time, is from here. There is a half-hour guided tour to the harem and only 15-20 people are taken on each tour. There was a long queue and so reluctantly we had to forego the harem visit. But, I have read much about the harems and the sex life of the Sultans from an interesting book that I bought in Istanbul. From what I have read, the harem is a labyrinth of interconnecting suites. It was the Sultan’s private home where his mother, his wives, his children and his concubines were housed. The Sultans had beautiful women from the East and the West. The entrance to the hrem was guarded by a corps of eunuchs who acted as go-betweens with the outside world into which the Sultan’s women were not allowed. Another interesting thing mentioned in the books is the cage rooms of the crown prince. The windows and doors of these rooms were secure against inevitable assassination attempts by younger claimants and their mothers.

We rushed back to the hotel to check out. We then caught a ferry from the Galata Bridge to the Hyderpasa Railway Station, a beautiful Victorian building which has been in service for more than a century. We left our backpack at the left-luggage center and went for a walk around the town. We then had a good lunch, the highlight of which was a bowl of very tasty yogurt. The train left exactly at 6:10 p.m.

Day 4

When the train left Hyderpasa station, there was only one more passenger in our compartment, a young Turk who had his nose in a newspaper for most of his journey. Our compartment was cozy with plush seats, head rests, and even a sliding door. I had picked up a copy of The Turkish Daily, the only English newspaper in the country. The headlines were about the Turkish troops battling the Kurdish guerillas in western Iraq. The Kurdish Party is a minority group that has been rebelling against the Turkish Government. The Turks are very fond of football, and the newspapers are filled with football news and photographs. I even noticed a newspaper in Turkish called Spor (for Sport, I guess) completely dedicated to football, and pictures of buxom women. This reminded me of the scandal-mongering Blitz newspaper of India, which we bought primarily for the pictures of half-naked belles on the back page.

Istanbul is a large city and it took a long while for the train to get out of the suburbs. The Turkish countryside, according to Vani, resembles rural India. I could not see much resemblance, though. There were no lush paddy fields, no stray dogs, no bullock carts and no half-naked farmers in their fields. And none squatting beside the tracks relieving themselves. She can probably see much deeper into the meaning of things.

As the train proceeded, we also started noticing the peculiar habits of the young Turk. He sat in a corner, although he had the whole berth to stretch out on and stooped over his newspaper for hours. He changed this position only when he smoked, which he did quite regularly. When he did, he seemed to make sure we partook of the incense. He closed the windows and the sliding door tight before he lit up. This started getting on our nerves. To reduce the asphyxiating effect, I pretended to go out, to open the sliding door. This did not work as he promptly closed it behind me. Finally, I could not take it any longer and told him that it was pretty stuffy inside and could I open the window. Suddenly, his face lit up and he gestured to say, by all means. He turned out to be a very helpful and gracious person. By 10 p.m. when Vani and I were very sleepy but awkwardly trying to find a suitable position, he opened up the sleepers, spread the blankets and the pillows (provided by the railways), and asked us to sleep more comfortably. The guidebooks mentioned the hospitable nature of the Turkish people. This and many other incidents proved the point.

Later, in another station, there was one more addition to our compartment — Abdulla, a college student, who was going back to Denizli, his hometown. Abdulla was silent for most of the time, preoccupied with his Walkman. However, in the morning when we woke up and were waiting for the Pamukkale stop, we tried talking to him to find out where to get down. Abdulla did not know much English and many times did not understand what we were asking him. Vani got on very well with him though, and talked to him for a long time, while I was mostly at the window trying to take pictures of the countryside in the early morning light. She gathered that we had to get down at Denizli, which was also the last stop for the express. At 8:30 a.m. when the train stopped at Denizli, Abdulla came along to show us where to catch a van to Pamukkale.

The passengers in the van were mostly tourists: a couple from Australia who immediately started talking to an Irishman, a French couple who were busy petting, and both of us watching all of them. The owner of the van, Ozger, spoke fluent English. He tried to sweet-talk us into staying in his motel in Pamukkale, with success too. Then there was this friend of Ozger who was talking to the Irishman loudly about his French girlfriend. He was saying that he does not have Turkish girlfriends as he would have to marry them. It was pretty blunt the way he put it, using the f-word often. The journey to the Pamukkale village took us about 30 minutes. We got down in front of the Ozger Motel with the Australian couple and Ozger. We checked into a double bedroom, which looked quite alright. Only when I went to the toilet to finish my morning ablutions that trouble started.

The toilet looked neat with new tiles. The flush, however, did not work, and this I realized only after I finished the job. Consumption of large amounts of tasty fish the previous day had resulted in a by-product that had an aroma that appeared to me so potent as to kill the whole village. I wonder why the stuff cannot be used for biological warfare. The air had to be cleared of the fragrance soon, or it might have proved fatal. I embarked on the task immediately, with Vani giving me verbal support from outside. But, there was no vessel to be found in the toilet. Being innovative, I saw in the dustbin a useful tool. I filled it with water from the sink faucet repeatedly to clear the debris. By dint of hard work I made the place as good as new.

There is a water problem in Pamukkale. Hot water is available in surplus in the pipes, may be because of the thermal springs. Cold water, however, is a scarcity. For Vani to finish her job less strenuously, I had to do something. I found a large, almost broken, plastic bucket lying in the yard. With the help of the bellboy, I filled it up with cold water from the swimming pool and brought it up to our room in the first floor. Hard work, but it would have been harder otherwise.

We finally left the motel to go to the thermal springs at around 12 noon. The weather here was very different from Istanbul’s, hot and sultry. So, we put on our shorts and t-shirts, and took our swimwear for what we expected to be an exhilarating thermal bath. But, it turned out quite differently. We decided to walk to the thermal springs as we were told that it was not very far from our motel. After walking for more than 30 minutes in the torrid heat, we realized we were misled. Desperately, we looked for a taxi, but we found none on the road as we waited. We then decided to hitchhike. We started waving at the cars zipping past us on the winding road. Finally, a car stopped and the couple inside invited us to get in. It took us about 10 minutes to reach the top of the hill where the lime deposits are situated. The couple had to pay a vehicle entrance fee at the gates. I offered to pay, but they declined. We got out of the car and thanked them. After they drove off, Vani noticed that I had forgotten my cap in the car. So, we did pay for the ride after all.

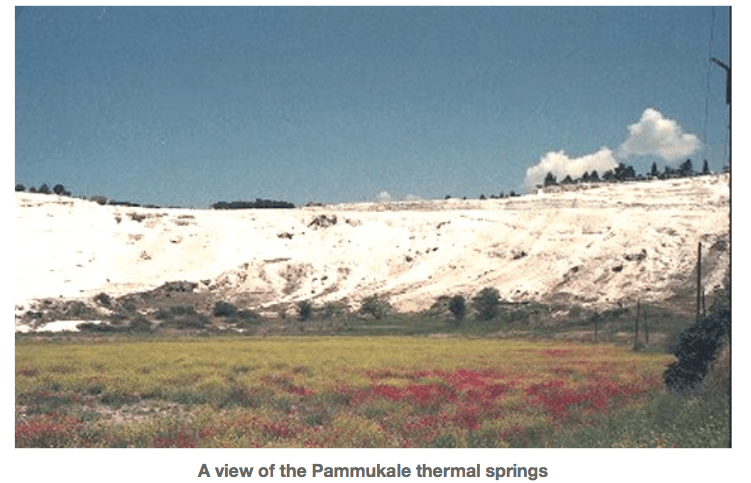

Pamukkale, in Turkish, means Cotton Castle. From far it looks just that. My guidebook says that for thousands of years an underground spring located deep in the earth has been pouring out streams of hot mineral-saturated water. As it has flowed down the mountain side the steaming water has hollowed enormous circular basins in the earth, and their rich mineral content has coated them in a smooth layer of dazzling-white calcareous rock. To the ancients such beauty could have meant that the place was holy. A grand city was built near it called Hirrapolis which attracted a steady stream of pilgrims who came to bathe in the curative waters. Now what remains of the city are the ruins of enormous pillars, cubes cut out of rocks to use as bricks, and gigantic boulders.

The hot springs consist of calcium-magnesium sulphate and bicarbonate, carbon dioxide, and are radioactive too. The water temperature is usually 36-38 degrees centigrade. My guidebook recommends the water for treatment of rheumatic, dermatological and gynecological diseases. And also for neurological and physical exhaustion. We were certainly physically exhausted by now, and were looking forward to soak in the warm waters. However, we were disappointed to hear that the authorities had stopped tourists from entering the waters for the last couple of days. Crestfallen, we thought of cooling off in a cafe nearby. It was evident that other tourists were very disappointed too. Two French women who were sitting beside our table were very angry about this. After eating a hearty meal, they got up and said they would not pay and the owner could call the police if he so desired. They walked off nonchalantly, shouting at the top of their voice. I was amazed at the way they pulled it off, but it was stupid of them to take their anger out on the innocent cafe owner.

We suddenly realized we had nothing much to do in Pamukkale. We decided that we would leave to Istanbul the same evening instead of the next day as we had planned earlier. The train would leave at 5:25 p.m. and it was already 2:30 p.m. We had to get back to the motel, check out, catch a bus to Denizli, change the railway tickets to today’s date, and get on the train in time, and to do all this we had less than 3 hours. By the time we could find a van that could take us back to the motel, it was already 3 p.m. Then the van waited for another 10 minutes for passengers to fill up. I had asked the driver to let us know when he reached the motel. The fellow had somehow forgotten in spite of my reminding him twice. And when I asked him again he said we had already gone past it. He was, however, nice enough to help us board another bus in the opposite direction. We reached the motel, checked out, boarded another bus to Denizli, and by the time we reached the train station it was around 4:30 p.m. At the counter we were told that there were no adjacent sleepers left. We either had to take sleepers which were in two different compartments, or settle for two adjacent chairs. We agreed to the latter and finally got into the train.

We thought our troubles were over, but not so soon. Just before the train started moving, Vani noticed that the dates on the tickets were wrong. According to it, we were supposed to be traveling two days later. Panic set in, but I suddenly became indifferent and aloof to everything. If it came to the worst, we might have to get down and go by bus, or leave the next day. However, when the conductor came and punched our tickets with not a second glance at it, Vani let a sigh of relief, and I was going, “I told you…”

Our seats were quite comfortable with exaggerated pushbacks. More comfortable than the aircraft seats that we had traveled in. The old mullah in the adjacent seat had with him, so I thought, two chubby wives, while Vani thought they were only his daughters. I had to enlighten her on their flair for taking on wives until ripe old age.

At 9 p.m. we went to the dining car for our dinner. I ordered raki, the Turkish alcoholic drink. It is a colorless liquid much like vodka, but when you add soda or tonic to it, it looks like buttermilk (as they call it in India). It tastes not unlike buttermilk too, sourish to quite a degree. The waiter could not understand English, and so an elderly man beside our table came to our rescue. It was very nice of him to recommend some good dishes and also what to eat with raki. We ordered pilav, mixed kebabs of chicken and lamb which were most delicious, and yogurt. Vani made mosaru-anna (curd-rice) out of the pilav and yogurt combination, and felt at home on a train thousands of miles away from home.

Day 5

We were back in the dining car in the morning for our breakfast. We sat at a table where there was a genial-looking old man. He greeted us with a perfunctory offer of cigarettes which we declined. I enjoyed sitting in the dining car, watching through the window blurred images of passing towns and villages. The old man was trying to make conversation with us in Turkish. We understood very little of what he said, nevertheless we nodded our heads in an engaging manner. Presently, the waiter brought us our coffee. The old man started mixing sugar and cream in Vani’s coffee, in spite of her asking him not to take the trouble. Here was a man who did not know who we were, from where we came and what we spoke, but had instantly showed a natural affection towards us. My five years of life in the taciturn, business-like Singapore had corrupted me. I had thought that the days of spontaneous friendship (that was so common in India) were over. The old man had reminded us of the most endearing human quality of all.

We reached Hyderpasa station in Istanbul around 9 a.m. We then caught a ferry to Eminonu just in front of the station. We had to look for a hotel to stay for two more days. My guidebook suggested some inexpensive places to stay, among which was the Optmist Guest House in Sultanahmet. We took a tram from Eminonu to Sultanahmet, and found the guesthouse just opposite the Hippodrome. The double bedroom and breakfast would cost us $15 a day. The guesthouse was a neat little place, with a stylish cafe in the front overlooking the Blue Mosque and the Ayasofya Museum. We had our brunch at the cafe watching package tourists getting off their buses in hordes and rushing off to see whatever they could in the short time they are allowed. We felt superior to them all for having the luxury of taking our time doing things that we liked and not being told around.

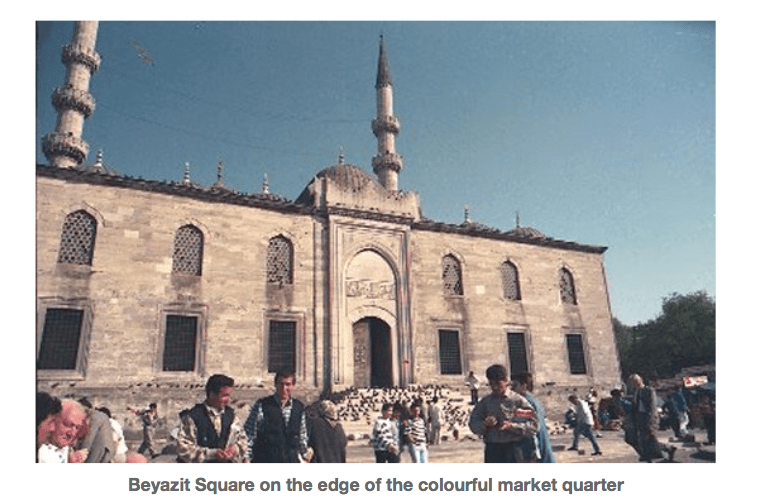

Today we wanted to visit the Princes’ Islands, also called Kizil Adalar. So, we made again, what appeared to be, one of our zillionth trips to the Eminonu ferry station. We bought our tickets first, and since the ferry would only after 45 minutes, we decided to have lunch. We were becoming gluttons. Just an hour ago we had a filling brunch of omelets, bread, coffee, etc. The cold weather and our constant walking made us feel famished all the time. We went to the Beyazit Square nearby to find an authentic Turkish food stall to eat. Beyazit Square is one of the city’s most fascinating public places. The pavements are sprawled with stalls of an open-air flea market. This place reminds one of Istanbul’s position as a natural market. Beside it is the famous Covered Bazaar, a labyrinth of 4000 shops. Its layout is still the same as when it was established in the 15th century, although it has been rebuilt several times after fires.

I was looking around for an interesting place to eat outside the bazaar. I saw one cafe which had many colorful food items displayed. We had a kind of yellowish red soup that tasted like dhal, a very squishy but tasty chicken dolma, pilav and Turkish bread. The waiter shocked us initially by giving us a bill of 4 million Turkish Lira when in fact it was only 400,000 Liras. Looked as though he had hoped that we would pay up without any question. As we walked up the gangplank of the ferry to Princes’ Islands, I yearned for a good snooze.

The journey to Buyukada, the largest and the last of the nine Princes’ Islands, takes an hour –and –a half. The island had been a place of exile and death where wild dogs rounded up in Istanbul were left to die, and convicts were sentenced to death. Now, the island has developed into a fashionable summer resort. There are no cars here according to my guidebook, although we did see a couple of them. There are horse-drawn carriages that make trips through the forested isle. We did not hire the carriages but went on foot. The walk was exhausting because of the undulating roads, but we got intriguing glimpses of wooden houses and views of the island and its shores. We saw a lot of cats, and saw one house which had more than twenty of them. The Turks seem to be very fond of these feline creatures as there are so many of them even in Istanbul. There were no dogs to be seen anywhere.

When we returned to Istanbul, we decide to go to a belly dance show in the evening. We inquired at a place but were told that we needed to book seats in advance. We came back to our guesthouse and asked Javed, the owner, about any other place he could suggest. Javed was a very pleasant and helpful person. He would answer your questions, however trivial, in detail. He tried getting us a place in one of the most authentic belly dance shows in Istanbul, the Galata Tower. Galata Tower is near the Galata Bridge that connects Europe and Asia over the Golden Horn waterway. The view from this tower is supposed to be magnificent. The show is considered to be the best in Istanbul. But we found the entrance fee of $120 too expensive, and we decided to have a leisurely night of good drinks instead. I bought a big bottle of gin, a couple of cans of tonic and a variety of cold Turkish hors-d’oeuvres for the long and intoxicating evening. It was late in the night, when our heads were woozy and the Hippodrome in front of the cafe empty except for a gang of rowdy youth playing football, we stumbled up the stairs of the guesthouse to our rooms for a much-needed night’s sleep.

Day 6

My previous day’s indulgence in gin had given me a groggy feeling and a recurrence of improbable images in my head. I was still in bed at 11 a.m. saying to myself things like “I’m not under the alkafluence of inkahol that some thinkle peep I am. It’s just the drunker I lie here the longer I get.” A hot shower followed by a cold one, and a hearty breakfast helped clear my head. By 12 noon we were ready for our last foray into Istanbul.

During breakfast we got talking to Javed, the guesthouse owner, again. He explained to us how to make Turkish coffee in minute detail. He also told us where to get good coffee powder. When I asked about some good Turkish audio cassettes to take home, he talked at length about the popularity of various Turkish singers. According to him, Mustafa is the most popular singer in Turkey now, admired and enjoyed by both the young and the old. We later bought a cassette of Mustafa and another one of a collection of Turkish folk music.

This was our last day in Istanbul and we decided to spend it more by strolling around at leisure rather than visiting historical monuments. But we had heard of an underground palace that was nearby that we could seeing finish quickly. The name of the palace is Yerebatan Sarayi. It is an eerie place built in the Byzantine period. The steep entrance stairway leads to a dimly lit underground forest of pillars. The dim lighting and the muffled classical music give a haunted feeling to the place. The pillars, interestingly, sit on some form of pagan heads upturned for some reason. I checked my guidebook and it said the upturned heads symbolize ‘discharging of power’ (?). Another thing that adds to the hauntedness of the place is the constant dripping of water from the ceiling. My guidebook says this was built in 532 AD as a cistern to supply water to the Byzantine palace and other buildings. Over the years the knowledge of the existence of the cistern was mysteriously lost, and it took an inquisitive Frenchman to rediscover it in 1545.

We spent sometime in an attached book house where I bought a couple of books and postcards. As we came out into the daylight again, a small boy smartly dressed in a checked shirt and pants started pestering us to buy his tops. The decorated tops had much blunter ends than the ones you see in India. We bargained playfully with him for sometime and bought one for 150,000 Lira. We spent the rest of the afternoon walking on foot, buying Turkish sweets, cassettes, and handicrafts.

Javed had agreed to drop us at the airport in his car on his way to his weekly football game. As the car moved slowly on the congested roads, we saw numerous Turkish families picnicking in the parks and gardens by the sides of the highways. The entire population of Istanbul seemed to be out on the streets enjoying themselves.

~*~