F

Authors: Michael Erb and Ranganatha Sitaram

1. Neuroscience and Meditation

Since the early sixties of the last century, neuroscientific

investigations of meditation have been performed with

electroencephalographic (EEG) recordings. Although

neuroelectric correlates of altered states of consciousness during

meditation are not yet firmly established, the primary findings

have implied increases in theta and alpha band power, and

decreases in overall frequency (for a review see Cahn & Polich

2006). With the development of neuroimaging techniques like

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and functional Magnetic

Resonance Imaging (fMRI) in the 80s and 90s, these new

methods have also been applied to reveal the neurophysiologic

correlates of modified self-experience in meditation practice.

For many years the 14th Dalai Lama Tendzin Gyatsho has been

interested in Western science. In 1987, a series of meetings—the

Mind and Life conferences—were initiated between the Dalai

Lama and a number of prominent neuroscientists. This led to

numerous neuroscience studies on meditation (Barinaga 2003)

including neuroimaging, especially at the University of

Wisconsin (Madison) surrounding the group of neuroscientist

Richard Davidson.

Unlike Western science, Buddhist philosophy assumes the

existence of six senses that allow the mind to interpret the world.

In addition to the senses of seeing, hearing, touch (body sense),

taste and smell, the sixth sense or inner sense allows us to

monitor our thoughts and feelings. Buddhism is therefore

viewed as a science of the mind with insights based on more than

2,500 years of studying the mind by introspection. Western

neuroscience may thus gain valuable insights from this

experience by adapting some of these practices in theoretical and

experimental investigations.

A fundamental question for neuroscience is the elucidation of the

relationship between subjective experience and neural firing. A

flash of light, for example, produces measurable evoked

potentials in the visual cortex. While it is relatively

straightforward to relate simple sensory stimuli to brain activity,

it is, however, far less obvious how complex subjective states

4 Neuroimaging Experiments on Meditation

such as the experience of meditation are reflected in brain

activity. Experimental approaches to meditation can be broadly

classified into two major types with different goals concerning

the states and traits of meditation (Cahn & Polich 2006). The

first one investigates the differences between the mental state in

normal day-to-day thinking, and the specific mental state during

an ongoing meditation session. The second approach investigates

the effect of meditation that persists even when not presently

engaged in meditation practice. Both approaches have provided

insight into the effects of meditation practice on the mind and

brain of humans.

2. The Tübingen Experiment on Śūnyatā meditation

In 2006, the Śūnyatā meditation center in Stuttgart (Germany)

contacted Dr. Michael Erb and asked if he would be interested in

conducting neuroimaging experiments on brain activity of the

Buddhist master of the school, Master Thích Thông Triệt, during

meditation in the MR scanner. After discussing the challenges

and scope of such an investigation and consulting with another

neuroscientist, Dr. Ranganatha Sitaram, the authors consented to

embark on a series of experiments to examine Śūnyatā

meditation with different levels of expertise. The aim of our

study was to investigate whether there are differences in brain

activations between meditation and normal day-to-day thinking.

And if so, we wanted to further identify brain activations

pertaining to different stages and techniques of Śūnyatā

meditation. The idea was to investigate whether specific brain

activity is related to different techniques of meditation.

Before discussing in more detail our hypotheses, an explanation

of the central doctrine of Śūnyatā meditation is useful for a better

understanding of the framework. Buddha described the methods

of meditation as follows (as per Bāhiya Sutta, Anderson 2002):

“Please train yourselves thus: In the seen, there will be just the

seen. In the heard, there will be just the heard. In the sensed,

there will be just the sensed. In the cognized, there will be just

the cognized. When for you, in the seen there is just the seen, in

the heard just the heard, in the sensed just the sensed, in the

cognized just the cognized, then you will not identify with the

seen, and so on. And if you do not identify with them, you will

not be located in them; if you are not located in them, there will

be no here, no there, or in-between. And this will be the end of

suffering.”

The word Śūnyatā means emptiness in Sanskrit. This meditation

practice has its origin in the Buddhist philosophy that signifies

the impermanent nature of form, or, in other words, that objects

in the world do not possess essential or enduring properties. In

Buddhist spiritual teaching, cultivating insight into emptiness

leads to wisdom and inner peace. Śūnyatā meditation practice is

aimed at developing an ability to avoid discursive (wandering,

long-winded) thought. Instead insight into the nature of reality is

acquired through direct perception of the internal (bodily) and

external (sensory) states. So, automatic associations of former

episodes from memory, evaluation of perceptions with respect to

ones’ own existence and planning of future actions will be

reduced, whereas self-awareness and awareness of the things in

the world will increase.

2.1 Hypothesis

The aim of the present study was to investigate state changes in

the brain and accompanying bodily reactions during Śūnyatā

meditation, when confronted with a variety of external stimuli.

Based on the rationale behind the Śūnyatā practice, we

hypothesized that the following state changes occur during

Śūnyatā meditation in comparison to normal day-to-day

thinking: First, brain regions that have been associated with

memory retrieval, planning and executive control will be

deactivated; second, brain areas related to interoception and

sensory perception will be activated; and third, the respiration

rate (and possibly other physiological signals) will be reduced.

As mentioned in the chapter on Biofeedback in Zen meditation,

the Buddhist doctrine is embodied in a practice of

meditation that guides the practitioner to “Not Naming the

Object” and rather helps him to “see it as seeing” (bare or natural

seeing), “hear it as hearing” (bare or natural hearing), “feel it as

feeling” (bare or natural touch) and “know it as knowing” (bare

or natural cognition).

We investigated the following four different meditative

practices: natural seeing, natural hearing, natural touch and

natural cognition. The objectives of the study were to identify

brain regions associated with the different sensory states of

meditation. In addition, we wanted to investigate whether there

were common activations across all these practices. This was

motivated by the idea that all practices are based on the Buddhist

doctrine explained above. We expected to find activations in

visual areas (occipital cortex) during natural seeing, in auditory

areas (temporal lobe) during natural hearing and somatosensory

areas (postcentral gyrus) during natural touch. We also expected

brain activations common to all meditation practices in the

temporo-parieto-occipital junction (e.g. Brodmann Area (BA)

39), which plays a role in multi sensory integration (Fig. 1).

Since 2006, we have scanned several meditators from the

Śūnyatā Meditation Stuttgart e.V. (Germany) and monks and

nuns from Śūnyatā Meditation Center in Riverside (CA, USA); a

total of 8 participants in 18 sessions, including 6 sessions with

Master Thích Thông Triệt.

In this chapter, we will present the findings from the group and a

few single cases and then focus on the results of the experiments

with the Master. It should be noted here that while the method

allows a description of brain activations elicited during

meditation, it is not suitable to investigate the effects of

meditation on the autonomic nervous system and physical health.

2.2 Measurement Methods

For a better understanding and interpretation of the results of our

experiments, it is necessary to provide a summary of the

capabilities and limitations of the neuroimaging approach used in

this study.

2.2.1 Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is currently one

of the most widely used methods for mapping human brain

functions. FMRI measures the hemodynamic response to neural

activity in the brain. This is possible because increased activity

in nerve cells also increases their consumption of oxygen. The

local response to this oxygen utilization is to increase blood flow

to regions of increased neural activity, which occurs after a delay

of approximately 1–5 seconds. This hemodynamic response rises

to its peak of intensity around 4–5 seconds, before falling back to

baseline (and typically undershooting slightly). Thus, neural

activity leads to local alterations in the relative concentration of

oxygenated hemoglobin and deoxygenated hemoglobin, cerebral

blood volume and blood flow. As hemoglobin is diamagnetic

when oxygenated and paramagnetic when deoxygenated, this

difference can be measured by magnetic susceptibility sensitive

MR sequences (e.g. echo planar imaging – EPI). The resulting

blood-oxygenation-level dependent signal (BOLD signal, Ogawa

1990) is an indirect measure of the corresponding neural activity.

In a typical fMRI experiment, the BOLD signal differences can

reach up to 5% of its baseline value, implying that these small

effects can only be detected by many fMRI measurement

volumes and sophisticated statistical analysis methods. The

standard design of fMRI experiments is the so-called block

design, where blocks with stimulation or task condition are

alternated with blocks of rest or control condition. As the length

of the hemodynamic response function (HRF) is about 15

seconds, conditions typically alter every 20 to 30 seconds to be

able to obtain multiple rises and falls of the response. With a

typical spatial resolution of 3 mm, it is possible to scan the

whole brain with EPI sequences in about 2-3 seconds, so that as

many as 10 brain volumes can be acquired within each block.

After averaging the measured volumes in all rest blocks and all

task blocks respectively, one can determine the difference

between these mean values to show locations with higher values

in task blocks above a selected threshold as overlays on

anatomical images, typically measured with a resolution of

1x1x1 mm3. A preliminary online analysis can be performed

immediately on the scanner computer during fMRI acquisition of

the experimental protocol. For refined analysis, there are several

statistical methods available such as modeling the expected

hemodynamic response and estimating parameters of a general

linear model with the measured data. In addition some

preprocessing steps like head motion correction, that is

realigning the images to the first volume, and smoothing of the

images can help to improve the statistical power of analysis.

Experimental protocol

We were confronted with two potential problems in the

experimental setup. One concerns the scanner environment

which is not optimal for meditation: the participants are placed in

a narrow scanner with considerable measurement noise. To

overcome this issue, it was important to have highly experienced

meditators who would be able to adjust to the situation. The

other problem is related to setting up suitable task and control

conditions. For the present experiment, it was doubted whether

meditators could achieve rapid switching between normal

thinking (control condition) and meditation (task condition)

within a few seconds. It was therefore decided to use longer

block lengths of alternating baseline (3 times of 2 minutes each)

and meditation (2 times of 3 minutes each) conditions (Fig. 2).

This was a reasonable trade-off between the requirements of

effective fMRI measurements and normal duration of meditation

sessions.

2.2.2 Physiological Signals

In addition to the BOLD signal, we recorded respiration and

pulse signals to calculate time courses of respiration amplitude

and frequency together with heart beat frequency. From these

signals, we tried to estimate the time course of actual meditative

states. There was no clear indication or previous data from

Śūnyatā meditation suggesting that respiration rate changed as a

consequence of the meditation state, or whether control of

respiration rate was used to reach the meditation state as in other

meditation practices.

After each session, participants were asked to rate the depth of

the meditative state achieved in each meditation block by using a

questionnaire.

2.2.3 Electroencephalography (EEG)

For some sessions, we were able to simultaneously record EEG

signals from 31 electrodes with a MR compatible EEG amplifier

and EEG cap (BrainAmp MR, Brain Products GmbH, Munich,

Germany). EEG measures the brain’s electrical activity directly,

while fMRI records changes in blood flow. Combining EEG and

fMRI allows for brain signals to be recorded at a high temporal

as well as spatial resolution. Lutz and colleagues (Lutz et al.

2004) have shown increased gamma oscillations during

meditation. We thus expected to classify different stages of

meditation with the help of EEG signals and use these time

courses to find corresponding locations in the fMRI signal.

It should be noted here that there are still technical difficulties

associated with combining fMRI and EEG measurement

techniques, including the need to remove the MRI gradient

artifacts present during MRI acquisition and the cardioballistic

artifact (resulting from the pulsative motion of blood and tissue)

from the EEG signals. These difficulties may interfere with data

interpretation.

2.3 Additional tasks

In addition to the meditation protocol described previously, we

performed an extended examination with the Master Thích

Thông Triệt with paradigms targeting object recognition and

language related areas, different levels of thinking, and the

differences between sensory stimulation and no stimulation

under normal thinking and meditation conditions. In these

sessions, we used a block design with blocks of 30 seconds each

for more efficient fMRI measurement. A further set of sessions

tested four different levels of awareness, namely, “verbal”,

“tacit”, “awakening” and “cognitive” awareness.

2.3.1 Visual and auditory naming of animals and tools

In the visual naming task, we projected pictures of animals and

tools onto a screen inside the MR scanner that was visible to the

participant via a mirror. The participant was instructed to name

the object using inner speech (without actual vocalization). As

we were only interested in regions engaged in object recognition

and naming and not primary visual processing, we showed

stimuli of scrambled images as control condition.

In the auditory naming task, we presented short sounds from

animals and tools to the participant with MR compatible

headphones. Each sound had a duration of 2.5 seconds and was

presented randomly two times in the experimental session. To

activate the primary auditory regions in a comparable way, we

used the same sounds but scrambled in the control periods.

Control and task periods were signaled to the participant with a

red or green rectangle, respectively. With these tasks, we wanted

to identify brain areas for object recognition and language.

Visual naming should activate the higher level of the ventral

visual stream including the fusiform gyrus (BA37, bilateral)

engaged in visual object recognition, as well as the language

areas for generating the corresponding nouns (Wernicke’s area,

BA22, BA39, BA40, left) and performing inner speech (Broca’s

area, BA44/45, premotor area, BA6, left). Auditory naming

should activate the superior temporal gyrus and again the

language and speech areas. Hence, with this approach, we

expected to identify the brain regions where we expected

changes in different meditation methods.

2.3.2 Different levels of thinking

To distinguish between different levels of thinking, we

conducted a series of sessions with the Master. The protocol

comprised 13 blocks with different thinking tasks (duration = 30

seconds), namely “intellect”, “mind-base”, and “consciousness”

in alternating order. These terms were displayed as written words

on the screen for the corresponding period of 30 seconds each

and were used as a trigger for the participant to invoke

“thinking.” “Intellect” corresponded to cognitive thinking and

reasoning, whereas the “mind-base” condition involved relaxed

playing around with thoughts (“inner chatter”) and

“consciousness” referred to being aware of the self. “Counting”

was used as a reference task as this can be done more or less

automatically.

2.3.3 Different levels of meditative depth (awareness)

In an additional series of sessions with the Master, four different

levels of meditation depth as per Buddha’s description were

investigated: “verbal awareness”1, “tacit awareness”2,

“awakening awareness”3 and “cognitive awareness”4. These

measurements were also performed in a block design of 2

minutes of baseline (3 times) and 3 minutes of meditation (2

times), as much faster switching between the levels could have

been difficult. Master Thích Thông Triệt characterized these

four states in the following way:

1. Verbal Awareness is equivalent to the first level of Samādhi,

or Savitakka Avicāra Samādhi, in the original teachings.

The inner silent dialogue, or vicāra, refers to the mental images

that arise from the memory during the sitting meditation. It

hinders the practice of meditation. To prevent the inner silent

dialogue from surfacing to consciousness, the Buddha taught

“silent thinking”, or avicāra, a meditation technique

characterized by silently thinking the phrase, “When I breath in,

I know I am breathing in; when I breath out, I know I am

breathing out”. This technique quiets the inner dialogue by

focusing the mind on the task of breathing. The practitioner then

experiences the state of “Vitakka without vicāra” Samādhi, or

verbal thinking but noninner-silent-dialogue Samādhi.

2. Tacit awareness, Avitakka Avicāra Samādhi, similar to the

second level of Samādhi, meaning “wordless thinking and

nondiscursive dialogue”.

Tacit awareness means wordless or non-verbal awareness. At

this state of awareness, the practitioner masters the chattering

mind during four common daily activities: walking, standing,

lying, and sitting. By quieting the mind, the practitioner

inactivates the networks of perception, one component of the

Five Aggregates which, according to the original meditation and

Zen sect, is the most important Samādhi. Through this level of

Samādhi, the practitioner is able to attain all the other levels of

meditation, such as Śūnyatā Samādhi, Formlessness Samādhi, or

Wishlessness Samādhi. This is in contrast to the tradition of The

Elders (Sthaviravadin) and Sarvastivadah. The Elders

commended mind concentration (Citta-ekkaggatā)

3. Awakening Awareness is equivalent to the third level of

Samādhi, Sati-Sampajañña, and is defined as the “full awareness

or clearly comprehensive awareness without attachment to the

objectives”.

Awakening awareness is different from Wakeful Awareness

which is characterized by the association of the Objective with

Consciousness. Awakening Awareness is a state of the mind

without the involvement of the subjective, yet the presence of the

Awareness only. The Buddhist Developers assumed the term

“true self” or “pure self” in which the practitioner attains

Samādhi in all four daily activities.

4. Cognitive Awareness is equivalent to the fourth level of

Samādhi.

At this stage, the mind is so tranquil that the delicate breathing

ceases from time to time. The Buddha calls it the “three

immobile or unshakeable formations” which refers to the (1)

standstill of the discursive thinking in which neither Vitakka nor

Vicāra arises, (2) the standstill of thoughts in which neither

feeling nor perception arises, and (3) the standstill of the body,

where the breathing stops occasionally. In fact, when the

practitioner reaches this stage of meditation, he can go in or out

of Samādhi at ease. In Theravada Sutras, the Buddha described

this status of Samādhi as “finger snapping Samādhi”. The sixth

Patriarch, Hui Neng, called it the “Samādhi needless to be in or

out.”

2.3.4 Different meditation tasks

As already mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, we

utilized four different methods of meditation, namely natural

seeing, natural hearing, natural touch and natural cognition. We

used control conditions very similar to the meditation tasks to

ensure sensitivity to the effects of specific meditation practices.

For the condition “seeing” one picture was displayed on the

screen in the control block (baseline, 2 minutes), when the

participant focused attention on the image and analyzed its

content (normal seeing). The same picture was used in the

following meditation block (3 minutes) with natural seeing.

Hence, the external input (stimulation) was exactly the same in

both conditions, the only difference being the mode of

processing of the input. In the same way, we played identical

music continuously over the MR compatible headphones in the

baseline condition and in the “natural hearing” condition. The

third condition “natural touch” consisted of brush strokes that

were applied every second to the right palm of the hand of the

meditator. Short beeps were used to pace the speed of the

strokes. The fourth condition “natural cognition” was without

any sensory stimulation. The start of a new block was signaled

by auditory instructions and visually by the words “Baseline”

and “Meditation”, respectively, in each run.

In order to test the different activations caused by the sensory

input, we conducted a series of measurement sessions in which

the external input (seeing, hearing, touch) was switched on and

off every 30 seconds. These sessions were repeated in the dayto-

day thinking and meditation condition.

2.4 Data analysis

Analysis of the fMRI data incorporated several steps. After

transferring the data to the local computer network and

converting them to a file format usable for the analysis program

package, the three dimensional volumes of each measurement

time point were realigned to the first volume of the session to

compensate for head movement over the whole measurement

period. This is very important because the subsequent analysis is

calculated for each volume element (voxel) separately.

Therefore, corresponding brain locations have to be in the same

position for the whole run. Unfortunately, this method can only

correct replacements between volumes and not distortions

caused by fast movements in the time period of the data

acquisition. Therefore, in the case of such fast movements, there

are still remarkable signal variations in the data after movement

correction. (This is the reason, why it is so important to fix the

head with a foam cushion inside the scanner while the fMRI

measurement is running.) In the case of group studies, it is

necessary to transform the individual’s brain images into a

standard coordinate system to ensure that corresponding brain

regions of the individual participants are in the same position in

the new datasets. One then can localize specific positions of

activations in computerized brain atlases and databases to locate

the precise anatomical region, and to compare with findings

from other experiments.

The standard data analysis programs used in analyzing fMRI

data typically estimate a general linear model (GLM) to the

measured signal time courses of small brain volume elements

(voxels) in order to ascertain which parts of the brain were

activated in the given task. The problem with this kind of

analysis is that the time course of task performance has to be

known. In our case, we could only use the time course defined

by our instructions. To also obtain an objective measure for the

meditative state, we used peripheral physiological signals and

EEG signals. The time course of the meditative state estimated

from the time courses of these different signals could then be

used to search for the corresponding time courses in fMRI

signals. This, however, is only possible if there is a direct and

constant relationship between the signals and the meditative

state, which is by itself an unresolved topic of research (e.g. Lutz

et al. 2004).

In a second approach, we used a data driven method, the socalled

independent component analysis (ICA, see Calhoun et al.

2009 for a review), which separates from the mixed signal timecourse

different spatial patterns of activations which are

statistically independent of each other and hence may have

originated in different sources. From these automatically

generated patterns, we had to sort out components with a time

course related to the task. This method allows identification of

constant activations over the whole meditation period as well as

transient time courses. Other components related to movement or

measurement artifacts may be used to correct the data.

2.5 Results

2.5.1 Analysis of the Physiological Signals

The analysis of the physiological signals revealed some

interesting effects. In one participant, the time course of

respiration showed a clear reduction in frequency and an

increase in amplitude in the meditation periods compared to

normal thinking periods (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, all other

participants did not show this effect. Still another participant

showed a reduction in variations in the meditation period but no

changes in amplitude or mean frequency (Fig. 3 right bottom).

Figure 4: Physiological signals: Interruption of respiration

In a session in which the Master performed natural cognition

meditation (Fig. 4), respiration was interrupted for about 15

seconds at the end of the first meditation block. This behavior

has frequently been cited as reflecting deep state meditation.

Analysis of pulse rates showed only small and unsystematic

effects. Unfortunately, it was generally not possible to reliably

infer the meditation state from the physiological signals.

2.5.2 EEG

Due to a number of technical problems, it was not possible to completely

remove the MRI gradient artifacts (Fig. 5 top). After filtering out

the remaining frequency components, we could determine a

small change in EEG amplitude in different frequency bands.

While we observed a decrease of beta activity in the meditation

period over left parietal and central electrode sites (CZ, CP1,

FC), beta activity was increased over the electrodes in right

central electrode sites (C4, F4) (Fig. 5 bottom). Preliminary

time-frequency analysis of the EEG signals pointed to increased

power in the lower alpha bands over frontal and parietal

electrode sites during meditation compared to normal thinking

conditions in the stimulus switching task.

2.5.3 fMRI

2.5.3.1 Group analysis

We first calculated average group results from all investigations

of the meditation condition. Although individual results were

quite different, we nevertheless found some interesting

activations and deactivations already in our preliminary analysis,

which assumed more or less the same activations over the whole

meditation periods (Fig. 6). There were higher activations in the

visual cortex while performing meditation in the seeing

condition, whereas highest activation in the hearing condition

was found in the left Heschl’s gyrus. Main activation in the

touch condition was located in the left insula, and the cognition

17 Neuroimaging Experiments on Meditation

task generated additional activations in regions of the parietal

lobes.

A more elaborate analysis method allowing transient time

courses of the BOLD-signal (the so called independent

component analysis, ICA) showed comparable results. We found

the following common activations and deactivations in all 4

different meditation types when contrasting meditation with

normal thinking (Fig. 7):

• activations in bilateral precuneus, implicated in selfprocessing

and consciousness (Cavanna 2007),

• activations in the bilateral insula, implicated in interoception

(Craig, 2009),

• deactivations in frontopolar region of the brain, namely,

BA10, involved in strategic processes including memory

retrieval and executive function, and

• deactivations in the posterior cingulate, implicated

consistently in the default network of brain function

(Raichle, 2001).

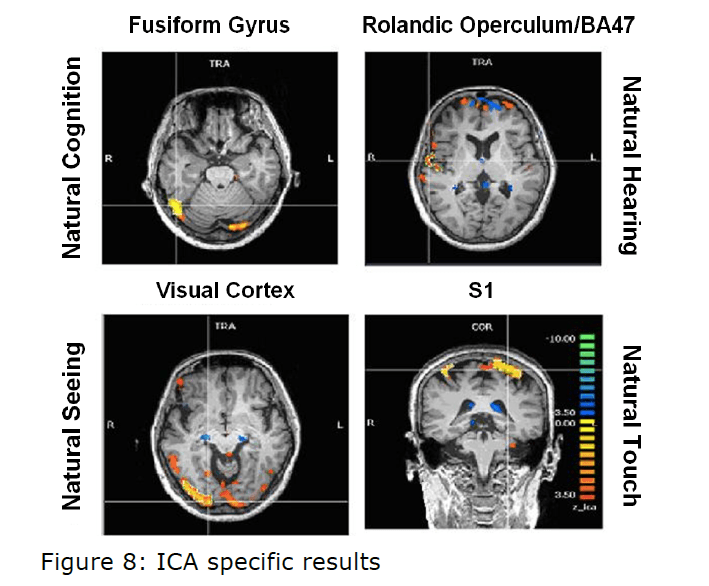

Activations pertaining to specific meditation types (meditation

versus normal thinking contrast) were as follows (Fig. 8):

1. enhanced activation of the fusiform gyrus (FFG) during

natural cognition meditation condition,

2. enhanced activation of the right rolandic operculum and

inferior frontal gyrus (BA 47) during the natural hearing

meditation condition,

3. enhanced activation of the visual cortex during the natural

seeing meditation, and

19 Neuroimaging Experiments on Meditation

4. enhanced activation in the somatosensory cortex during the

natural touch meditation condition.

2.5.3.2 Individual analysis from experiments with the Master

Thích Thông Triệt

Some experiments were only performed with Master Thích

Thông Triệt as he is able to reach deeper and more intense states

of mind.

Visual and auditory Naming of animals and tools

Figure 9: Visual (red) and auditory (green) naming (Master

top, group bottom) left: common activation in the right IFG

With the visual and auditory naming task (Fig. 9), we could

identify differentially activated regions in visual and auditory

association areas and common activations in language areas

(Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas). In particular, we found in the

visual naming condition activations in the bilateral visual cortex

in the ventral stream consisting of middle occipital gyri (BA 18,

BA 19), fusiform gyri (BA37), inferior temporal gyri, and

middle temporal gyri. These structures are associated with object

recognition and form representation. Further, the cerebellum (IX,

X) and inferior parietal lobes were activated prominently in the

right hemisphere. In contrast to these regions, the superior

temporal gyri lighted up only in the auditory naming task.

Regions common to both tasks were the triangular part of the

right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and the left superior temporal

gyrus (BA22, BA42). As the Master is right-handed, a right

dominance of language processing has low probability but is still

possible. In more than 95% of right-handed men and more than

90% of right-handed women, language and speech is sub served

by the brain’s left hemisphere, but in left-handed people, the

incidence of left-hemisphere language dominance has been

reported as 73% and 61% [Knecht 2000]. However, one should

exercise caution in concluding that this difference compared to a

group of 12 right-handed students is an effect of meditation.

Different levels of thinking

The first analyses of these sessions (Fig. 10) demonstrated

common activations in the posterior end of the right middle

temporal lobe and the angular gyrus (BA39). This area is

implicated in the integration of multimoldal data and

interpretation of written words (Damasio 1994). Persinger and

colleagues (2001) have shown, that out-of-body experiences and

mystic experiences could be triggered, if the region of the

temporal lobe is stimulated with transcerebral weak complex

magnetic fields. The experimental condition “intellect” showed

activations in the dorsolateral superior frontal gyrus. Commonly

activated regions with “intellect” and “mind-base” condition

activate the right triangular part of the inferior frontal gyrus

(Broca’s area, BA 44/45) and the brain regions to the left and

right precentral gyrus (premotor cortex, BA6). Brain areas

involved in “conscious” thinking were mainly constrained to the

temporal and parietal lobe. It is important to note, that the area

within BA 44/45 common to “intellect” and “mind-base”

thinking is in the same region, but not at the same position as the

area in the right frontal lobe that was found to be commonly

activated by the visual and auditory naming task.

Different levels of meditation depth (levels of Awareness)

Analysis of these different meditation levels (Fig. 11) showed a

decrease of activation in the left and right superior temporal

gyrus (STG) and an increase of activation in the left higher

visual areas (BA 18/19), the right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG),

the right insula and right cerebellum (Crus1). Inspecting the four

different “glass” brains (maximum intensity projection, MIP)

(Fig. 10, bottom) one notices a widespread global increase in the

occipital lobe for cognitive awareness.

Different Meditation tasks with and without stimulation

In our first experimental protocol (section 2.2.1), external

stimulation was held constant to elicit only the differences

between normal thinking and meditation. In the currently

reported experiment, the design was changed so that the brain

state was kept constant (either baseline or meditation), while the

external stimulation was switched on and off. For this

experiment, we used a design with 11 blocks of 30 seconds

resulting in a session length of 5 minutes 30 seconds. Each of the

three tasks “seeing”, “hearing” and “touch” were performed two

times, first with normal thinking and in the next run with

meditation. Comparing the activations induced in these two

sessions, we identified differences in processing external stimuli

in the different brain states.

In the “seeing” session (Fig. 12, left), we found activated regions

in the primary visual cortex on both sides, the left cerebellum

and left fusiform gyrus, the right supramarginal gyrus and

inferior parietal lobe (BA40) and the middle and superior frontal

gyrus (BA10). In the “hearing” condition (Fig. 12, middle), we

identified the main activations in left and right superior temporal

gyri (BA22/42) and in the left frontal operculum (BA44/45). In

the “touch” condition (Fig. 12, right), we found activations in

left insula and rolandic operculum and in right postcentral gyrus,

the primary somatosensory area. We generally observed a

smaller amplitude in the meditation condition compared to

normal thinking in all three primary sensory areas. This can be

interpreted as reduced sensitivity to changes of external

stimulation in the meditative state. Two explanations are

possible, that is either the gain of the external input is decreased

or the level of activation is maintained by “filling up” with

internal generated activity.

It was not possible to find a comparable design for the

“cognition” condition as there was no external input. Therefore,

we decided to use a design with 1 minute blocks of normal

thinking and meditation without external input and simultaneous

concentrating on “seeing”, “hearing”, “touch” and “cognition”.

This fast switching between the two states was only possible

with a very experienced meditator as Master Thích Thông Triệt.

When the blocks were only 30 seconds long, he experienced

problems leaving the meditative state. We thus settled for 60

second blocks. In this session, the online evaluation already

provided some findings. However, more sophisticated analysis

including the consideration of movement parameters resulted in

less (false positive) activated regions. Nevertheless, we could

identify regions in the visual (occipital lobe, BA17, BA19),

auditory (Heschl’s gyrus, BA41) and somatosensory (BA3) areas

showing enhanced activation in the meditation state compared to

the control state.

3. Conclusions

Our results show that Śūnyatā meditation enhances perception of

external stimuli and interoception of internal bodily states, as

shown by heightened activations in sensory areas and the insula

when compared to the normal, day-to-day thinking state in

sessions with long meditation periods (3 minutes) and constant

external input. In the sessions with fast changes of external

stimuli (30 seconds), the pattern was reversed: brain activation

was reduced in the primary sensory areas in the meditation state

compared to intellectual thinking. This can be explained by an

additional activation in the time periods without external

stimulation in the meditation state as was found in the cognitive

condition. If this supplementary activation is not purely additive,

that is the enhancement of activation with external stimuli is

smaller than the inserted activation without external stimuli, it

will result in a reduced difference (Fig. 14).